Thread by Thread

Essays by Prairie Stuart-Wolff

At the Helm

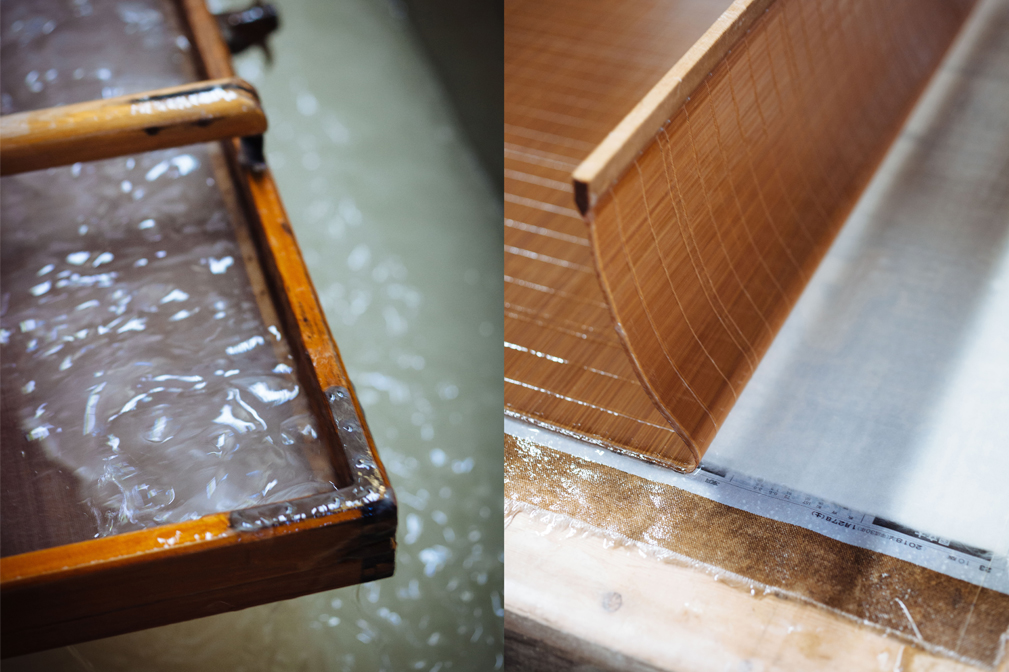

Toshihiro Tanaka grips a large wooden frame strung like a marionette to flexible rods of bamboo overhead. He takes a deep breath before dipping it into the reservoir below. There is musicality to his movements as he guides a solution of fibers made from the bark of kozo, the paper mulberry tree, suspended in water across a screen inside the frame.

“When I was young, I was so concentrated on technique, on how to run the screen through the water. Back then an ideal of movement was my singular desire,” he says. “Now I’m in tune with the materials, feeling and sensing as I go.” His body rocks in rhythm with the ripples. “When I become one with the water’s movement, there is no better feeling than that.” He rests the frame on supports and opens it, pausing to allow the newly formed sheet of washi paper a moment to touch the air and settle into being. Tanaka’s evolution as a craftsman is distilled in this brief hesitation.

Working alongside his wife and aging parents, Tanaka heads the only surviving family business in this washi producing region of the Tango peninsula that once saw hundreds of households making paper. He has been an eyewitness to the changing social landscape of his locale, one that mirrors nationwide trends. A flood of imported raw kozo fibers grown overseas forced many domestic growers out of business. And though the climate of his region is particularly well suited to growing good kozo for washi, Tanaka too saw his locally farmed supply dwindle. He was forced to reconsider the future. He noticed how the widespread use of imported materials by paper makers across the country had all but erased regional differences in washi. “When we considered how to survive as a small family operation we thought, we have to make a product that doesn’t exist anywhere else.When we asked ourselves what that might be, we thought back to when kozo was grown in the local earth and made into paper with local water. That is a product that cannot be made anywhere else, cannot be replicated.”

Kozo is a sustainable crop; all the branches of a single plant can be harvested in winter and will regenerate fully the next summer. It takes a decade to establish a robust kozo field but through hard work and patience, Tanaka can now make paper year round using entirely only his own homegrown materials. With so much of his time and efforts turned to growing his own kozo, he experienced a profound shift in perspective. “I started thinking primarily about the materials, about how to make the best use of homegrown kozo’s natural properties to make the best quality paper,” he explains. He felt compelled to slow down, to facilitate a process he had once tried to dictate. “Rather than control the movement of the water, I started to align my movements to the natural movements of the water and make paper born of that harmonious expression.” And in doing so he felt inspired to pause, to allow the newborn paper a moment to take its first breath before rotating it overhead and releasing it onto a growing stack of washi behind him.

A family business that survives centuries is like a ship, with each successive generation taking a shift at the helm. As the fifth generation to lead, Tanaka has drawn on the experiences of his predecessors to navigate the particular challenges of his own era. His grandfather developed and produced a single product, a very thin, gauze-like washi used by lacquer artisans to filter their lacquer before application. But demand fell and colorfully dyed washi products sold in department stores throughout Japan defined his father’s era. This brought recognition to his family’s product but the reign of the department store is ending. Tanaka has worked towards the self sufficient production of un-dyed washi used for calligraphy and in traditional buildings. His papers are used in the restoration and repair of many cultural properties including the Katsura Imperial Villa and the Kyoto Imperial Palace. “I think ultimately preserving tradition is not just simply conveying the exact things of the past into the future,” he says. “We make products that are contemporary with the current times. In doing so you pass through your own era and then pass the baton onto the next. That is how you preserve the tradition.”

Tanaka’s softly translucent ivory sheets of washi are warm, a strong and flexible paper that will last centuries. Though he knows his paper will live on, he cannot say what the future holds for his craft. His is but one stage in a relay tasked with safely delivering the flame of tradition to the next. “There is no completion,” he says, “no perfection or flawlessness. In my time if I can just continue to improve, if I can look back at the paper I made now, then at 60, then at 70, and say little by little it got better, if in the end it’s like that, that would be good I think.”