Thread by Thread

Essays by Prairie Stuart-Wolff

Greeting the New Year

Windows and doors are opened for a deep year-end cleaning, the rooms and halls as chilly as the late December day. The Irori room smells fresh with the scent of new tatami, green and grassy, a pristine start for the New Year. Outside, the garden pathways are carpeted in amber pine needles. A Camellia reaches bud-laden branches toward the window offering a few wide-eyed blossoms; their petals flush crimson like cold cheeks in winter.

Throughout the building rooms are abuzz with activity, bodies moving briskly to beat the cold. These final days of the passing year are a time to restore and revitalize the premises. Repairs are made. An expert in the art of earthen walls stands on a ladder to mend a crack above a doorway. He feathers wet clay with a small brush, intent upon a precise color match. Fissures are an inevitable result of our modern comforts as the building strains from internal and external environments at odds. Warm on one side and cool on the other, the walls expand and contract unsynchronized.

Upstairs, three craftsmen versed in the art of washi applications replace panels of Japanese paper. One inspects the shoji, looking for tears in the paper screens. He measures and cuts before brushing glue onto the wooden frame and setting the new pane of washi in place. Two others replace lengths of paper that run like baseboard where walls meet floors. “You don’t want beautiful fabrics of kimono brushing against the abrasive wall,” one explains as he applies wheat starch glue to a slip of paper. The other sets it in place. With broad strokes of his brush he adheres the paper and begins tapping with the bristles to bring out texture.

The kitchen too is as cold as the deep winter air outside. It is kept this way, unheated, to preserve an array of ingredients as head chef leads his team of chefs, bundled in layers of fleece and down, in preparing osechi, Japan’s celebratory and symbolic New Year’s meal. Designing a new osechi offering was his first challenge when he took the reigns as head chef and each year he continues to refine the more than fifty differently flavored morsels layered into three tiered plain cedar boxes. Osechi, prepared in advance, requires a unique approach to seasoning, he tells me. He must gauge how the flavors will mellow over time and calculate the right intensity to reveal a perfect flavor on New Year’s Day.

The chefs work around the clock. Day becomes night and soon day again.

At four in the morning on the penultimate day of the year the long lacquer table in the Hiroma room is laden with dozens of finished osechi meals ready to wrap. Ingredients gathered at their prime from mountains, fields, and sea offer a repertoire of flavors from throughout the year. Each taste harkens bygone seasons and anticipates their return. And there in the central tier a celebratory spread of signature Taiza crab, with flaky snow white meat encased in a dazzling red shell, rings in a festive mood.

To venerate the day, simple packaging is prepared in accordance with ceremonial offerings. Two looped willow branches bearing a profusion of buds anticipate good fortune in abundance. A slip of paper inscribed with a verse of auspicious literary symbols offers a benediction of boundless grace and favor. This poetic prelude invokes the blessings of osechi to be found inside. Unwrap the fresh green bamboo chopsticks and you’ll find them still cool to the touch, tapered at both ends to serve foods of the mountain and foods of the sea respectively. Untie the supple twine that secures a shroud of soft, thick housho paper. The wrapping falls away to reveal more willow boughs lightly traced in gold.

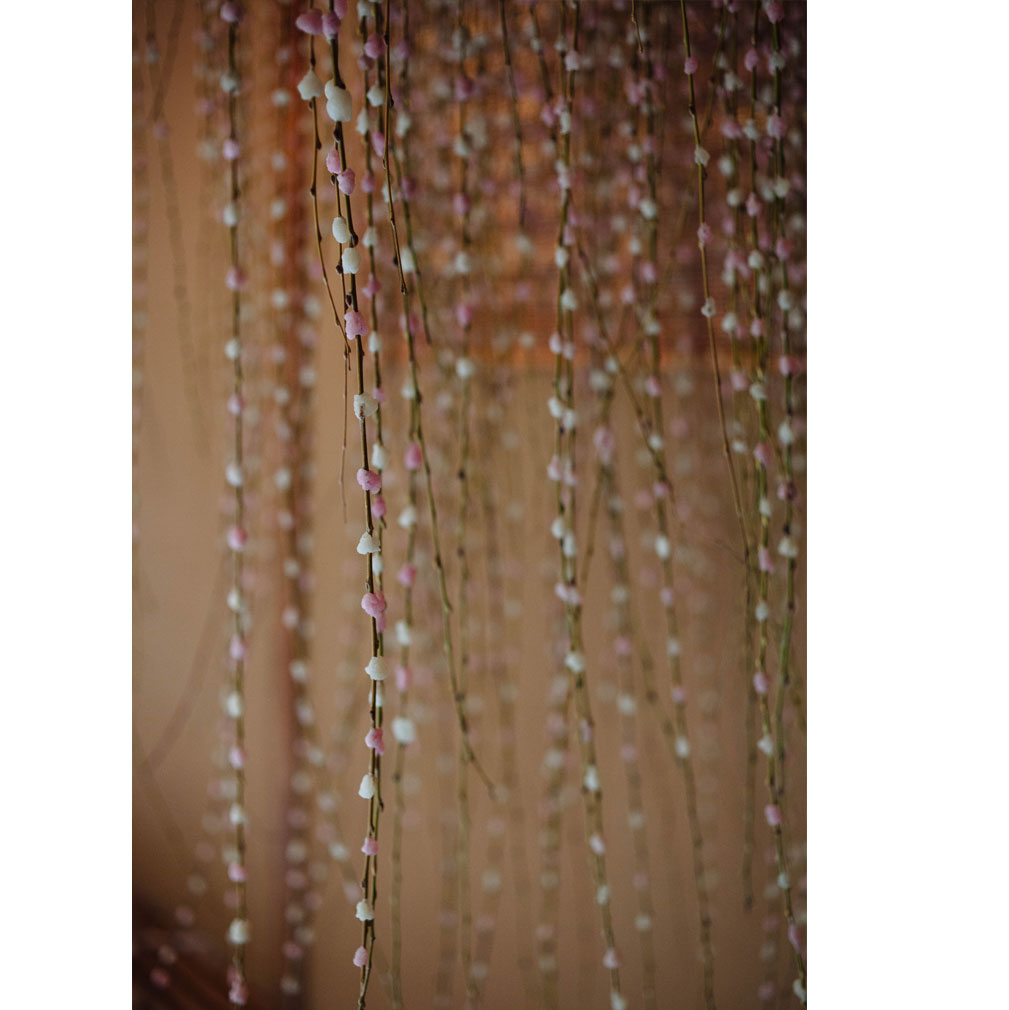

As day breaks, the kitchen is put back in order for one last evening service. The chefs retire for a short rest as cleaning continues. Winter light fades quickly and in the first dimming of evening a young attendant lights paper lanterns at the entrance. The breeze of her kimono rustles a spray of cascading weeping willow boughs dotted in pink and white. In the dark of winter, as fields lie fallow, farming families press these buds of mochi onto bare branches, their thoughts turned to the faint and distant glow of spring on the horizon. These visions of blossoms arranged at the entrance offer prayers for fair weather to yield bountiful harvests in the New Year.